“Sentence Completion” technique (for egocentrism). To the psychologist's piggy bank

PAT is a compact modified version of G. Murray's Thematic Apperception Test 1, which takes little time for examination and is adapted to the working conditions of a practical psychologist. A completely new stimulus material has been developed, which consists of contour plot pictures. They schematically depict human figures.

Murray's original test is a set of black and white tables with photographs of paintings by American artists. The pictures are divided into 10 male (intended for examining men), 10 female (intended for examining women) and 10 general. There are a total of 20 pictures in each set.

In addition, there is a children's set of pictures (CAT test), represented by 10 pictures, some of which are also included in the adult version of the technique.

TAT is one of the most in-depth personality tests 2. The absence of rigidly structured stimulus material creates the basis for a free interpretation of the plot by the subject, who is asked to write a story for each picture, using his own life experience and subjective ideas. The projection of personal experiences and identification with any of the heroes of the composed story allows us to determine the sphere of conflict (internal or external), the relationship between emotional reactions and rational attitude to the situation, the background of mood, the position of the individual (active, aggressive, passive or passive), the sequence of judgments, the ability to plan one’s activities, the level of neuroticism, the presence of deviations from the norm, difficulties in social adaptation, suicidal tendencies, pathological manifestations and much more. The great advantage of the technique is the non-verbal nature of the presented material. This increases the number of degrees of choice for the subject when creating stories.

During the research process, the person being examined outlines his stories (one, two or more) for each picture for 2–3 hours. The psychologist carefully records these statements on paper (or using a tape recorder), and then analyzes the subject’s oral creativity, identifies unconscious identification, identification of the subject with one of the characters in the plot and transfers his own experiences, thoughts and feelings into the plot (projection).

Frustrating situations are closely related to the specific environment and circumstances that can follow from the corresponding picture, either contributing to the fulfillment of the needs of the heroes (or hero), or preventing it. When determining significant needs, the experimenter pays attention to the intensity, frequency and duration of the subject’s fixation of attention on certain values repeated in different stories.

The analysis of the data obtained is carried out mainly at a qualitative level, as well as with the help of simple quantitative comparisons, which makes it possible to assess the balance between the emotional and rational components of the personality, the presence of external and internal conflict, the scope of broken relationships, the position of the individual - active or passive, aggressive or passive ( in this case, a ratio of 1:1, or 50 to 50%, is considered as the norm, and a significant advantage in one direction or another is expressed in ratios of 2:1 or more).

Noting separately the different elements of each plot, the experimenter summarizes the answers reflecting a tendency to clarify (a sign of uncertainty, anxiety), pessimistic statements (depression), incompleteness of the plot and lack of perspective (uncertainty in the future, inability to plan it), the predominance of emotional responses (increased emotivity) etc. Special themes present in large numbers in the stories are death, serious illness, suicidal intentions, as well as disrupted sequence and poor logical coherence of plot blocks, the use of neologisms, reasoning, ambivalence in assessing “heroes” and events, emotional detachment, diversity of perception of pictures, stereotypy can serve as serious arguments in identifying personal disintegration.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

A simplified version of the thematic apperception test is the one we developed. PAT method(drawn apperception test). It is convenient for studying the personal problems of a teenager. With the help of identification and projection mechanisms, deep-seated experiences that are not always controllable by consciousness are revealed, as well as those aspects of internal conflict and those areas of disturbed interpersonal relationships that can significantly influence the behavior of a teenager and the educational process.

Stimulus material techniques (see Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 ) presented 8th contour drawings depicting 2, less often 3, people. Each character is depicted in a conventional manner: neither his gender, nor age, nor social status is clear. At the same time, the poses, the expression of gestures, and the particular arrangement of the figures allow us to judge that each of the pictures either depicts a conflict situation, or two characters are involved in complex interpersonal relationships. Where there is a third participant or observer of events, his position can be interpreted as indifferent, active or passive.

The stimulus material of this technique is even less structured than in TAT. The era, cultural and ethnic characteristics are not visible here, there are no social shades that are clearly visible in the TAT pictures (subjects’ responses to some of them: “American soldiers in Vietnam”, “Trophy film”, “Hairstyles and foreign style fashion of the 20s " etc.). This clearly interferes with the subject’s direct perception, distracts, makes it possible to produce cliché-type answers (taken from films or other well-known sources) and contributes to the subject’s closeness in the experiment.

The drawn apperception test, due to its brevity and simplicity, has found application in examining schoolchildren and in family counseling, especially in conflict situations related to the problem of difficult adolescents. It is not recommended to use the technique on children under 12 years of age.

The positive side of the PAT test is that examination using this technique can be carried out simultaneously on a whole group of children, including in the classroom.

PROGRESS OF THE INVESTIGATION

The examination is carried out as follows.

The subject (or a group of subjects) is given the task to examine each picture sequentially, according to numbering, while trying to give free rein to their imagination and compose a short story for each of them, which will reflect the following aspects:

1) What is happening at the moment?

2) Who are these people?

3) What are they thinking and feeling?

4) What led to this situation and how will it end?

There is also a request not to use well-known plots that can be taken from books, theatrical performances or films, that is, to invent only your own. It is emphasized that the object of the experimenter’s attention is the subject’s imagination, the ability to invent, and the wealth of fantasy.

Usually, each child is given a double notebook sheet, on which, most often, eight short stories are freely placed, containing answers to all the questions posed. To prevent children from feeling limited, you can give two of these sheets. There is also no time limit, but the experimenter urges the children to get more immediate answers.

In addition to analyzing stories and their content, the psychologist is given the opportunity to analyze the child’s handwriting, writing style, manner of presentation, language culture, vocabulary, which is also of great importance for assessing the personality as a whole.

Protective tendencies can manifest themselves in the form of somewhat monotonous plots where there is no conflict: we can talk about dancing or gymnastic exercises, yoga classes.

WHAT THE STORIES TELL ABOUT

1st picture provokes the creation of stories that reveal the child’s attitude to the problem of power and humiliation. To understand which of the characters the child identifies with, you should pay attention to which of them in the story he pays more attention to and attributes stronger feelings to, gives reasons justifying his position, non-standard thoughts or statements.

The length of the story also largely depends on the emotional significance of a particular plot.

2, 5 and 7th pictures are more associated with conflict situations (for example, family), where difficult relationships between two people are experienced by someone else who cannot decisively change the situation. Often a teenager sees himself in the role of this third party: he does not find understanding and acceptance in his family, suffers from constant quarrels and aggressive relationships between mother and father, often associated with their alcoholism. At the same time, the position third party may be indifferent ( 2nd picture), passive or passive in the form of avoidance of interference ( 5th picture), peacekeeping or other attempt to intervene ( 7th picture).

3rd and 4th pictures more often provoke the identification of conflict in the sphere of personal, love or friendly relationships. The stories also show themes of loneliness, abandonment, frustrated need for warm relationships, love and affection, misunderstanding and rejection in the team.

2nd picture most often causes an emotional response in emotionally unstable adolescents, reminds of meaningless outbursts of uncontrollable emotions, while about 5th pictures More plots are constructed that involve a duel of opinions, an argument, the desire to blame another and justify oneself.

Argumentation of one’s rightness and the subjects’ experience of resentment in stories about 7th picture are often resolved by mutual aggression between the characters. What matters here is which position prevails in the hero with whom the child identifies himself: extrapunitive (the accusation is directed outward) or intropunitive (the accusation is directed towards oneself).

6th picture provokes aggressive reactions of the child in response to the injustice he subjectively experiences. With the help of this picture (if the subject identifies himself with a defeated person), the sacrificial position, humiliation is revealed.

8th picture reveals the problem of the object’s rejection of emotional attachment or flight from the annoying persecution of the person he rejects. A sign of identifying oneself with one or another character in a story is the tendency to attribute plot-developed experiences and thoughts to precisely that character who in the story turns out to belong to the same gender as the subject. It is interesting to note that with equal conviction the same pictorial image is recognized by one child as a man, by another as a woman, while each has complete confidence that this cannot raise any doubts.

“Look how she sits! Judging by the pose, this is a girl (or girl, woman),” says one. “This is definitely a boy (or a man), you can see right away!” says another. In this case, the subjects look at the same picture. This example once again clearly demonstrates the pronounced subjectivity of perception and the tendency to attribute very specific qualities to the very amorphous stimulus material of techniques. This happens in those individuals for whom the situation depicted in the picture is emotionally significant.

Of course, an oral story or additional discussion of written stories is more informative, but during a group examination it is more convenient to limit yourself to a written presentation.

The interpersonal conflict, which sounds in virtually every picture, not only makes it possible to determine the zone of disturbed relationships experienced by the child with others, but often highlights a complex intrapersonal conflict.

So, a 16-year-old girl, based on the 4th picture, constructs the following plot: “He declared his love to the girl. She answered him: “No.” He's leaving. She is proud and cannot admit that she loves him, because she believes that after such a confession she will become a slave to her feelings, and she cannot agree to this. He will suffer in silence. Someday they will meet: he is with someone else, she is married (although she does not love her husband). She has already gotten over her feeling, but he still remembers her. Well, so be it, but it’s calmer. She is invulnerable."

There is a lot of personal stuff in this story that doesn’t follow from the picture. The external conflict is clearly secondary and is based on a pronounced intrapersonal conflict: the need for love and deep affection is frustrated. The girl is afraid of possible failure. Painful pride, developed on the basis of negative life experiences, blocks free self-realization and spontaneity of feelings, forces her to give up love, so as not to increase the level of already high anxiety and self-doubt.

When studying the problems of a teenager in family situations, RAT clearly identifies his position. It is unlikely that a teenager himself could tell a better story about himself: self-understanding and life experience at this age are at a fairly low level.

Self-understanding and awareness of one’s own role in complex conflicts of everyday situations are also poorly expressed in children with a high level of neuroticism, emotionally unstable or impulsive.

In this regard, psychological research using RAT contributes to a more targeted choice of psychocorrectional approach, not only with a focus on the content side and sphere of the subject’s experiences, but also with an appeal to a certain linguistic and intellectual-cultural level of the personality of the child being consulted by a psychologist.

Lyudmila SOBCHIK,

Doctor of Psychology

1 G. Murray. Personality. N.Y., 1960.

2 Leontyev D.A. Thematic apperception test. M.: Smysl, 1998.

After the Second World War, the test began to be widely used by psychoanalysts and clinicians to work with disorders in the emotional sphere of patients.

Henry Murray himself defines TAT as follows:

“Thematic Apperception Test, better known as TAT, is a method with which one can identify dominant impulses, emotions, attitudes, complexes and conflicts of the personality and which helps to determine the level of hidden tendencies that the subject or patient hides or cannot show due to their unconsciousness”

- Henry A Murray. Thematic apperception test. - Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1943.

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 1

Measuring Personality: Crash Course Psychology #22

Subtitles

How would you describe your personality? Friendly, creative, quirky? What about nervous, shy or outgoing? But has anyone ever called you sanguine? What about Kapha, or full of metal? The ancient Greek Doctor Hippocrarian believed that personality manifested itself through four different fluids, and you are a personality due to the balance between phlegm, blood, yellow and black bile. Following Traditional Chinese Medicine, our personalities depend on the balance of the five elements: earth, air, water, metal, and fire. Those who follow traditional Hindu Ayurvedic medicine see everyone as a unique combination of three different mind-body principles called Doshas. Sigmund Freud believed that our personalities depend in part on who wins the battle of impulses between the id, ego, and superego. At the same time, humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslov suggested that the key to self-realization lies in successfully climbing the hierarchy of more basic needs. And now there are BuzzFeed tests to determine what type of pirate, shifter, sandwich, or Harry Potter character you are, but I wouldn't pay much attention to these. All this to say, people have been trying to characterize each other for a long time, and maybe you prefer blood, or bile, or ego, or id, or sandwiches, there are many ways to describe and measure personality. All these theories, all the years of research, cigar smoking, ink blot staring, and fans speculating whether they are Luke or Leia, all come down to one important question. Who, or what, is one's own personality? Introduction Last week we talked about how psychologists often study personality by looking at the differences between characteristics, and how these various characteristics combine to create a complete thinking and feeling person. Early psychoanalysts and humanistic theorists had many ideas about personality, but some psychologists question their lack of clearly measurable standards. for example, there is no way to actually translate into numbers the response to inkblots, or how much they are orally fixed. This movement toward more scientific approaches gave birth to two better-known theories of the twentieth century, known as the trait perspective and social cognitive theory. Instead of focusing on lingering subconscious influences or missed developmental opportunities, trait theory researchers attempt to describe personality in terms of stable and enduring patterns of behavior and conscious motivators. According to legend, it all started in 1919, when a young American psychologist, Gordon Allport, visited Freud himself. Allport was telling Freud about his train journey here, and how there was a little boy who was obsessed with cleanliness and didn't want to sit next to anyone or touch anything. Allport wondered if the child's mother had a phobia of dirt that affected him. Blah blah blah, he tells his story and at the end Freud looks at him and says "Mmm...were you that little boy?" And Allport said, "No, man, it was just a kid on a train. Don't turn this into some subliminal episode from my repressed childhood." Allport believed that Freud dug too deep, and sometimes one only needs to look at motives in the present rather than the past to explain behavior. So Allport started his own club, describing personality in terms of fundamental traits, or characteristic behaviors and conscious motives. He was less interested in explaining traits than in describing them. Modern trait researchers like Robert McCrae and Paul Sost have since organized our fundamental traits into the famous Big Five: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism, which you may remember by their initials OSEDN. Each of these characteristics exists on a spectrum, so for example, your level of openness may range from complete openness to new experiences and variety on the one hand, or a preference for a strict and regular routine on the other. Your level of conscientiousness may reflect impulsiveness and carelessness, or caution and discipline. Someone high in extraversion will be outgoing, while those on the other side will be shy and quiet. A very friendly person is helpful and trusting, while someone on the opposite end is distrustful or unfriendly. And on the spectrum of neuroticism, an emotionally stable person will be calm and balanced, while a less stable person will be worried, unbalanced, and self-pitying. The important idea here is that these characteristics are considered to be predictive of behavior and attitudes. for example, an introvert may prefer to communicate via email more than an extrovert; a friendly person is more likely to help a neighbor move the sofa than a suspicious person watching others through a window. By maturity, these characteristics become fairly stable, as scientists would tell you, but that doesn't mean they can't flex a little in different situations. The same modest person can start singing Elvis karaoke in a crowded room in a certain situation. So our personality traits are better predictors of our average behavior rather than our behavior in any given situation, and research shows that some traits like neuroticism are better predictors of behavior than others. This flexibility that we all possess leads to the fourth prominent theory of personality, the social cognitive perspective. First proposed by our Bobo-beating friend Alfred Bandura, the school of social cognitive theory emphasizes the interactions between our traits and their social context. Bandura noted that we learn many of our behaviors by observing and imitating others. This is the social part of the equation. But we also think about how these social events influence our behavior, which is the cognitive part. Thus, people and their situations work together to create behavior. Bandura called this type of interaction mutual determinism. For example, the kind of books you read, the music you listen to, your friends - all of these say something about your personality because different people choose different environments, and then these environments continue to influence the affirmation of our personalities. So if Bernice has an anxious-suspicious personality, and she has an intense and titanic crush on Sherlock Holmes, she will be especially careful in potentially dangerous or strange situations. The more she sees the world this way, the more anxious and suspicious she becomes. thus, we are both the creators and the results of the situations with which we surround ourselves. This is why one of the key indicators of personality in this school of thought is the sense of personal control - that is, how much control you feel you have over your environment. Those who believe in their ability to control their destiny or create their own luck have an internal locus of control, and those who feel that they are driven by forces beyond their control have an external locus. Are we talking about control and helplessness, introversion and extroversion, calmness and anxiety? , or whatever, each of these diverse perspectives on personality has its own methods of testing and measuring personality. We've already talked about how the psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach used the ink blot test to infer information about a person's personality, and we know that Freud used dream analysis, and he and Jung were both fans of free association, but the more extended school of theorists now famous Like the psycho-dynamic school emanating from Freud and friends, other projective psychological tests are also used, including the famous Thematic Apperception Test. In this type of testing, you will be shown evocative but vague pictures and asked to explain them. You may also be asked to tell a story about the pictures, taking into account how the characters feel, what is happening, what happened before this event, or what will happen next. For example, does a woman cry because of the death of her brother or because of a bee sting? Or is it a maid laughing because some rich guy passed out drunk on his bed, or maybe the object of her fiery love just confessed his love to her in the heat, Jane Austen style, and she's panicking in the hallway?! The idea is, that your answers will reveal something about your worries and motivations in real life, about the way you see the world, about your subconscious processes that drive you. Contrasting with this approach, modern personality researchers believe that it is possible to measure personality using a set of questions. There are many so-called personality trait inventories. Some take a short reading of a specific stable trait, such as anxiety or self-esteem, while others measure a large number of traits, such as the Big Five. These tests, like the Myers Briggs you may have heard of, include a lot of true-false or agree-disagree questions such as "Do you like being the center of attention?" “Is it easy for you to understand the pain of others?” “Is justice or forgiveness important to you?” But the classic Minnesota Multidimensional Personality Inventory is probably the most used personality test. The most recent version asks a set of 567 true-false questions, from “Nobody understands me” to “I like technology magazines” to “I loved my father,” and is often used to measure emotional illness. There are also methods from Bandura’s social cognitive school. Because this school of teaching focuses on the interaction of environment and behavior, not just traits, they don't just ask questions. Instead, they can measure personality across different contexts, with the understanding that behavior in one situation is better predicted by how you behaved in a similar situation. for example, if Bernice got scared and tried to hide under the table during the last five thunderstorms, you can predict that she will do this again. And if we conducted a controlled laboratory experiment where we studied the effects of thunderstorm sounds on people's behavior, we might gain a better understanding of the underlying psychological factors that may predict thunderstorm fear. and finally, there are humanistic theorists like Maslov. They often completely deny standardized testing. Instead, they measure your understanding of yourself through therapy, interviews, and questionnaires that ask people to describe how they would like to be and who they actually are. The idea is that the closer the present is to the ideal, the more positive the self-image. Which brings us back to the most important question of all: what or who is this self? All those books about self-esteem, self-help, self-understanding, self-control and the like are built on the idea that the personality controls thoughts and feelings and behavior: and in general is the center of a person. But of course, this is a tricky problem. You can think of yourself as a concept of several personalities - an ideal self, perhaps a devastatingly beautiful and intelligent, successful and loved, and maybe a scary self - which can be left without a job and alone and devastated. This balance of potential best and worst selves motivates us through life. At the end of the day, when you consider the influence of environment and childhood experiences, culture and all that, without mentioning biology, which we haven't even talked about today, can we really describe ourselves? or even answer with confidence that we have a personality? this, my friend, is one of the most difficult questions in life, still without a universal answer. But you still learned a lot today, right? We talked about trait and social cognitive theories, and we also talked about the many ways these and other schools measure and test personality. what I am and how our self-esteem works. Thanks for watching, especially to all our Subbable subscribers who help keep this channel going. If you want to know how to become a subscriber, visit subbable.com/crashcourse. This series was written by Kathleen Yale, edited by Blake de Pastino, and consulted by Dr. Ranjit Bhagavat. Our director and editor is Nicholas Jenkins, our copy director is Michael Aranda, who is also our sound designer, and our graphics team is Thought Café.

History of the creation of the technique

The thematic apperception test was first described by K. Morgan and G. Murray in 1935. In this publication, TAT was presented as a method for studying imagination, allowing one to characterize the personality of the subject due to the fact that the task of interpreting depicted situations, which was posed to the subject, allowed him to fantasize without visible restrictions and contributed to the weakening of psychological defense mechanisms. The TAT received its theoretical justification and a standardized scheme for processing and interpretation a little later, in the monograph “Study of Personality” by G. Murray and his colleagues. The final TAT interpretation scheme and the final (third) edition of the stimulus material were published in 1943.

Testing process

The test taker is offered black and white drawings, most of which depict people in everyday situations. Most TAT drawings depict human figures whose feelings and actions are expressed with varying degrees of clarity.

TAT contains 30 paintings, some were drawn specifically at the direction of psychologists, others were reproductions of various paintings, illustrations or photographs. In addition, the subject is also presented with a white sheet on which he can imagine any picture he wants. From this series of 31 drawings, each subject is usually presented with 20 in succession. Of these, 10 are offered to everyone, the rest are selected depending on the gender and age of the subject. This differentiation is determined by the possibility of the subject identifying himself with the character depicted in the drawing to the greatest extent, since such identification is easier if the drawing includes characters close to the subject in gender and age.

The study is usually carried out in two sessions, separated by one or more days, in each of which 10 drawings are presented sequentially in a certain order. However, modification of the TAT procedure is permitted. Some psychologists believe that in a clinical setting it is more convenient to conduct the entire study at one time with a 15-minute break, while others use part of the drawings and conduct the study in 1 hour.

The subject is asked to come up with a story for each picture, which would reflect the situation depicted, tell what the characters in the picture think and feel, what they want, what led to the situation depicted in the picture, and how it will end. Answers are recorded verbatim, recording pauses, intonations, exclamations, facial and other expressive movements (stenography, a tape recorder may be used, or less often the recording is entrusted to the subject himself). Since the subject is unaware of the meaning of his answers regarding seemingly foreign objects, he is expected to reveal certain aspects of his personality more freely and with less conscious control than under direct questioning.

The interpretation of TAT protocols should not be carried out “in a vacuum”; this material should be considered in relation to the known facts of the life of the person being studied. Great importance is attached to the training and skill of the psychologist. In addition to knowledge of personality and clinical psychology, he must have significant experience with the method; it is advisable to use this method in conditions where it is possible to compare the TAT results with detailed data on the same subjects obtained by other means.

Interpretation of results

G. Lindzi identifies a number of basic assumptions on which the interpretation of TAT is based. They are quite general in nature and practically do not depend on the interpretation scheme used. The primary assumption is that by completing or structuring an incomplete or unstructured situation, the individual manifests his aspirations, dispositions and conflicts. The following 5 assumptions are related to identifying the most diagnostically informative stories or fragments thereof.

- When writing a story, the narrator usually identifies with one of the characters, and that character's desires, aspirations, and conflicts may reflect the desires, aspirations, and conflicts of the narrator.

- Sometimes the narrator's dispositions, aspirations, and conflicts are presented in implicit or symbolic form.

- Stories have unequal significance for diagnosing impulses and conflicts. Some may contain a lot of important diagnostic material, while others may contain very little or no material at all.

- Themes that are directly implied by the stimulus material are likely to be less salient than themes that are not directly implied by the stimulus material.

- Recurring themes are most likely to reflect the narrator's impulses and conflicts.

Finally, 4 more assumptions are related to inferences from the projective content of stories concerning other aspects of behavior.

- Stories can reflect not only stable dispositions and conflicts, but also actual ones related to the current situation.

- Stories can reflect events from the past experience of the subject in which he did not participate, but witnessed them, read about them, etc. At the same time, the very choice of these events for the story is associated with his impulses and conflicts.

- Stories can reflect, along with individual, group and sociocultural attitudes.

- The dispositions and conflicts that may be inferred from stories are not necessarily manifest in behavior or reflected in the mind of the storyteller.

In the vast majority of schemes for processing and interpreting TAT results, interpretation is preceded by the isolation and systematization of diagnostically significant indicators based on formalized criteria. V. E. Renge calls this stage of processing symptomological analysis. Based on the data of symptomological analysis, the next step is taken - syndromic analysis according to Range, which consists of identifying stable combinations of diagnostic indicators and allows us to move on to the formulation of diagnostic conclusions, which represents the third stage of interpretation of the results. Syndromological analysis, unlike symptomological analysis, lends itself very little to any formalization. At the same time, it inevitably relies on formalized data from symptomological analysis.

Literature

- Leontyev D. A. Thematic apperception test // Workshop on psychodiagnostics. Specific psychodiagnostic techniques. M.: Publishing house Mosk. Univ., 1989 a. P.48-52.

- Leontyev D. A. Thematic apperception test. 2nd ed., stereotypical. M.: Smysl, 2000. - 254 p.

- Sokolova E. T. Psychological research of personality: projective techniques. - M., TEIS, 2002. - 150 p.

- Gruber, N. & Kreuzpointner, L.(2013). Measuring the reliability of picture story exercises like the TAT. Plos ONE, 8(11), e79450. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079450 [Gruber, H., & Kreuspointner, L. (2013). Measuring the reliability of PSE kak TAT. Plos ONE, 8(11), e79450. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079450]

(TAT) is a method of complex in-depth psychodiagnostics of personality, belongs to the category of projective methods. developed in the second half of the 1930s. at the Harvard Psychological Clinic by G. Murray and his associates. TAT is a set of 31 tables with black and white photographic images on thin white matte cardboard. One of the tables is a blank white sheet.

(TAT) is a method of complex in-depth psychodiagnostics of personality, belongs to the category of projective methods. developed in the second half of the 1930s. at the Harvard Psychological Clinic by G. Murray and his associates. TAT is a set of 31 tables with black and white photographic images on thin white matte cardboard. One of the tables is a blank white sheet.

The subject is presented in a certain order with 20 tables from this set (their choice is determined by the gender and age of the subject). His task is to compose plot stories based on the situation depicted on each table. TAT is recommended for use in cases that raise doubts, require subtle differential diagnosis, as well as in situations of maximum responsibility, such as when selecting candidates for leadership positions, astronauts, pilots, etc. It is recommended to be used in the initial stages of individual psychotherapy, since it allows you to immediately identify psychodynamics, which in ordinary psychotherapeutic work become visible only after a fair amount of time. TAT is especially useful in a psychotherapeutic context in cases requiring acute and short-term treatment (for example, depression with suicidal risk).

The subject is presented in a certain order with 20 tables from this set (their choice is determined by the gender and age of the subject). His task is to compose plot stories based on the situation depicted on each table. TAT is recommended for use in cases that raise doubts, require subtle differential diagnosis, as well as in situations of maximum responsibility, such as when selecting candidates for leadership positions, astronauts, pilots, etc. It is recommended to be used in the initial stages of individual psychotherapy, since it allows you to immediately identify psychodynamics, which in ordinary psychotherapeutic work become visible only after a fair amount of time. TAT is especially useful in a psychotherapeutic context in cases requiring acute and short-term treatment (for example, depression with suicidal risk).

this is a specific diagnostic technique developed by G. Murray; this is a method of personal diagnostics, the embodiment of which is not only the Murray test, but also a number of its variants and modifications, developed later, as a rule, for more specific and narrow diagnostic or research tasks.

this is a specific diagnostic technique developed by G. Murray; this is a method of personal diagnostics, the embodiment of which is not only the Murray test, but also a number of its variants and modifications, developed later, as a rule, for more specific and narrow diagnostic or research tasks.

A complete examination using TAT rarely takes less than 1.5 - 2 hours and, as a rule, is divided into two sessions, although individual variations are possible. In all cases when the number of sessions is more than one, an interval of 1-2 days is made between them. If necessary, the interval may be longer, but should not exceed one week. At the same time, the subject should not know either the total number of paintings or the fact that at the next meeting he will have to continue the same work - otherwise he will unconsciously prepare plots for his stories in advance. At the beginning of the work, the psychologist places no more than 3-4 tables on the table (image down) in advance and then, as needed, takes out the tables one at a time in a pre-prepared sequence from the table or bag. An evasive answer is given to the question about the number of paintings; at the same time, before starting work, the subject must be determined that it will last at least an hour. The subject should not be allowed to look at other tables in advance.

A complete examination using TAT rarely takes less than 1.5 - 2 hours and, as a rule, is divided into two sessions, although individual variations are possible. In all cases when the number of sessions is more than one, an interval of 1-2 days is made between them. If necessary, the interval may be longer, but should not exceed one week. At the same time, the subject should not know either the total number of paintings or the fact that at the next meeting he will have to continue the same work - otherwise he will unconsciously prepare plots for his stories in advance. At the beginning of the work, the psychologist places no more than 3-4 tables on the table (image down) in advance and then, as needed, takes out the tables one at a time in a pre-prepared sequence from the table or bag. An evasive answer is given to the question about the number of paintings; at the same time, before starting work, the subject must be determined that it will last at least an hour. The subject should not be allowed to look at other tables in advance.

The general situation in which the survey is carried out must meet three requirements: 1. All possible interference must be excluded. the examination should be carried out in a separate room, into which no one should enter, the telephone should not ring, and both the psychologist and the subject should not rush anywhere. The subject should not be tired, hungry or under the influence of passion.

The general situation in which the survey is carried out must meet three requirements: 1. All possible interference must be excluded. the examination should be carried out in a separate room, into which no one should enter, the telephone should not ring, and both the psychologist and the subject should not rush anywhere. The subject should not be tired, hungry or under the influence of passion.

2. The subject must feel quite comfortable. The subject should sit in a position that is comfortable for him. The optimal position of the psychologist is from the side, so that the subject sees him with peripheral vision, but does not look at the notes. It is considered optimal to conduct the examination in the evening after dinner, when the person is somewhat relaxed and the psychological defense mechanisms that provide control over the content of fantasies are weakened. Secondly, the psychologist, through his behavior, must create an atmosphere of unconditional acceptance, support, approval of everything that the subject says, while avoiding directing his efforts in a certain direction. In any case, it is recommended to praise and encourage the subject more often (within reasonable limits), while avoiding specific assessments or comparisons. The psychologist should be friendly, but not excessively, so as not to cause heterosexual or homosexual panic in the subject. The best atmosphere is one in which the patient feels that he and the psychologist are seriously doing something important together that will help him and is not at all threatening

2. The subject must feel quite comfortable. The subject should sit in a position that is comfortable for him. The optimal position of the psychologist is from the side, so that the subject sees him with peripheral vision, but does not look at the notes. It is considered optimal to conduct the examination in the evening after dinner, when the person is somewhat relaxed and the psychological defense mechanisms that provide control over the content of fantasies are weakened. Secondly, the psychologist, through his behavior, must create an atmosphere of unconditional acceptance, support, approval of everything that the subject says, while avoiding directing his efforts in a certain direction. In any case, it is recommended to praise and encourage the subject more often (within reasonable limits), while avoiding specific assessments or comparisons. The psychologist should be friendly, but not excessively, so as not to cause heterosexual or homosexual panic in the subject. The best atmosphere is one in which the patient feels that he and the psychologist are seriously doing something important together that will help him and is not at all threatening

3. The situation and behavior of the psychologist should not actualize any motives or attitudes in the subject. Implies the need to avoid updating any specific motives in a survey situation. It is not recommended to appeal to the abilities of the subject, to stimulate his ambition, to show a pronounced position of an “expert human scientist”, or dominance. The professional qualifications of a psychologist should inspire confidence in him, but in no case should he be placed “above” the subject. When working with a subject of the opposite sex, it is important to avoid unconscious coquetry

3. The situation and behavior of the psychologist should not actualize any motives or attitudes in the subject. Implies the need to avoid updating any specific motives in a survey situation. It is not recommended to appeal to the abilities of the subject, to stimulate his ambition, to show a pronounced position of an “expert human scientist”, or dominance. The professional qualifications of a psychologist should inspire confidence in him, but in no case should he be placed “above” the subject. When working with a subject of the opposite sex, it is important to avoid unconscious coquetry

Work with TAT begins with the presentation of instructions. The subject sits comfortably, determined to work for at least an hour and a half, several tables (no more than 3-4) lie face down at the ready. The instructions consist of two parts. The first part of the instructions must be read verbatim by heart, twice in a row, despite possible protests from the subject.

Work with TAT begins with the presentation of instructions. The subject sits comfortably, determined to work for at least an hour and a half, several tables (no more than 3-4) lie face down at the ready. The instructions consist of two parts. The first part of the instructions must be read verbatim by heart, twice in a row, despite possible protests from the subject.

The text of the first part of the instructions: “I will show you pictures, you look at the picture and, starting from it, make up a story, a plot, a story. Try to remember what needs to be mentioned in this story. You will say what kind of situation you think this is, what kind of moment is depicted in the picture, what is happening to people. In addition, you will say what happened before this moment, in the past in relation to him, what happened before. Then you will say what will happen after this situation, in the future in relation to it, what will happen later. In addition, it must be said how the people depicted in the picture or any of them feel, their experiences, emotions, feelings. And you will also say what the people depicted in the picture think, their reasoning, memories, thoughts, decisions.” This part of the instructions cannot be changed (with the exception of the form of addressing the subject - “you” or “you” - which depends on the specific relationship between him and the psychologist)

The text of the first part of the instructions: “I will show you pictures, you look at the picture and, starting from it, make up a story, a plot, a story. Try to remember what needs to be mentioned in this story. You will say what kind of situation you think this is, what kind of moment is depicted in the picture, what is happening to people. In addition, you will say what happened before this moment, in the past in relation to him, what happened before. Then you will say what will happen after this situation, in the future in relation to it, what will happen later. In addition, it must be said how the people depicted in the picture or any of them feel, their experiences, emotions, feelings. And you will also say what the people depicted in the picture think, their reasoning, memories, thoughts, decisions.” This part of the instructions cannot be changed (with the exception of the form of addressing the subject - “you” or “you” - which depends on the specific relationship between him and the psychologist)

Second part of the instructions: After repeating the first part of the instructions twice, you should state the following in your own words and in any order: there are no “right” or “wrong” options, any story that matches the instructions is good. You can tell it in any order. It is better not to think through the entire story in advance, but to immediately start saying the first thing that comes to mind, and changes or amendments can be introduced later, if there is a need for this; literary processing is not required; the literary merits of the stories will not be assessed. The main thing is to make it clear what we are talking about.

Second part of the instructions: After repeating the first part of the instructions twice, you should state the following in your own words and in any order: there are no “right” or “wrong” options, any story that matches the instructions is good. You can tell it in any order. It is better not to think through the entire story in advance, but to immediately start saying the first thing that comes to mind, and changes or amendments can be introduced later, if there is a need for this; literary processing is not required; the literary merits of the stories will not be assessed. The main thing is to make it clear what we are talking about.

After the subject confirms that he understood the instructions, he is given the first table. If any of the five main points (for example, the future or the thoughts of the characters) are missing from his story, then the main part of the instructions should be repeated again. The same can be done again after the second story, if not everything is mentioned in it. Starting from the third story, the instructions are no longer recalled, and the absence of certain points in the story is considered as a diagnostic indicator. If the subject asks questions like “Have I said everything?”, then they should be answered: “If you think that’s it, then the story is finished, move on to the next picture, if you think that it’s not, and something needs to be added, then add "

After the subject confirms that he understood the instructions, he is given the first table. If any of the five main points (for example, the future or the thoughts of the characters) are missing from his story, then the main part of the instructions should be repeated again. The same can be done again after the second story, if not everything is mentioned in it. Starting from the third story, the instructions are no longer recalled, and the absence of certain points in the story is considered as a diagnostic indicator. If the subject asks questions like “Have I said everything?”, then they should be answered: “If you think that’s it, then the story is finished, move on to the next picture, if you think that it’s not, and something needs to be added, then add "

When resuming work at the beginning of the second session, it is necessary to ask the subject if he remembers what to do and ask him to reproduce the instructions. If he correctly reproduces the main 5 points, then you can start working. If some points are missed, you need to remind “You forgot...”, and then get to work without returning to the instructions. Murray suggests giving a modified instruction in the second session with an increased emphasis on freedom of imagination: “Your first ten stories were wonderful, but you limited yourself too much to everyday life. I would like you to take a break from it and give more freedom to your imagination.” Finally, after completion story on the last, twentieth table, Murray recommends going through all the stories written and asking the subject what the sources of each of them were - whether the story was based on personal experience, on material from books or films read, on the stories of friends, or is it pure fiction. This information does not always provide anything useful, but in a number of cases it helps to separate borrowed stories from the products of the subject’s own imagination and thereby roughly assess the degree of projectivity of each story.

When resuming work at the beginning of the second session, it is necessary to ask the subject if he remembers what to do and ask him to reproduce the instructions. If he correctly reproduces the main 5 points, then you can start working. If some points are missed, you need to remind “You forgot...”, and then get to work without returning to the instructions. Murray suggests giving a modified instruction in the second session with an increased emphasis on freedom of imagination: “Your first ten stories were wonderful, but you limited yourself too much to everyday life. I would like you to take a break from it and give more freedom to your imagination.” Finally, after completion story on the last, twentieth table, Murray recommends going through all the stories written and asking the subject what the sources of each of them were - whether the story was based on personal experience, on material from books or films read, on the stories of friends, or is it pure fiction. This information does not always provide anything useful, but in a number of cases it helps to separate borrowed stories from the products of the subject’s own imagination and thereby roughly assess the degree of projectivity of each story.

Latent time - from the presentation of the picture to the beginning of the story - and the total time of the story - from the first to the last word. The time spent on clarifying questioning is not added to the total time of the story. Position of the painting. For some paintings, it is unclear where the top is and where the bottom is, and the person being examined can turn it around. The rotations of the painting must be recorded. Relatively long pauses during the composing of the story.

Latent time - from the presentation of the picture to the beginning of the story - and the total time of the story - from the first to the last word. The time spent on clarifying questioning is not added to the total time of the story. Position of the painting. For some paintings, it is unclear where the top is and where the bottom is, and the person being examined can turn it around. The rotations of the painting must be recorded. Relatively long pauses during the composing of the story.

The complete set of TAT includes 30 tables, one of which is a blank white field. All other tables contain black and white images with varying degrees of uncertainty. The set presented for examination includes 20 tables; their choice is determined by the gender and age of the subject. The table provides a brief description of all the paintings. The symbols VM indicate pictures used when working with men over 14 years old, the symbols GF - with girls and women over 14 years old, the symbols BG - with teenagers from 14 to 18 years of both sexes, MF - with men and women over 18 years old. The remaining pictures are suitable for all subjects. The number of the painting determines its ordinal place in the set.

The complete set of TAT includes 30 tables, one of which is a blank white field. All other tables contain black and white images with varying degrees of uncertainty. The set presented for examination includes 20 tables; their choice is determined by the gender and age of the subject. The table provides a brief description of all the paintings. The symbols VM indicate pictures used when working with men over 14 years old, the symbols GF - with girls and women over 14 years old, the symbols BG - with teenagers from 14 to 18 years of both sexes, MF - with men and women over 18 years old. The remaining pictures are suitable for all subjects. The number of the painting determines its ordinal place in the set.

1 Speech stamps and quotes. The fact of their use is regarded as reduced energy of thinking, a tendency to save intellectual resources through the use of ready-made formulas. For example, instead of describing a person, they say “Jacklondon type” or “Hemingway type.” This also includes the frequent use of proverbs, sayings, and sayings. An abundance of cliches and quotes may also indicate difficulty in interpersonal contacts. The boy looks at the violin lying on the table in front of him. Attitude towards parents, the relationship between autonomy and submission to external demands, achievement motivation and its frustration, symbolically expressed sexual conflicts.

1 Speech stamps and quotes. The fact of their use is regarded as reduced energy of thinking, a tendency to save intellectual resources through the use of ready-made formulas. For example, instead of describing a person, they say “Jacklondon type” or “Hemingway type.” This also includes the frequent use of proverbs, sayings, and sayings. An abundance of cliches and quotes may also indicate difficulty in interpersonal contacts. The boy looks at the violin lying on the table in front of him. Attitude towards parents, the relationship between autonomy and submission to external demands, achievement motivation and its frustration, symbolically expressed sexual conflicts.

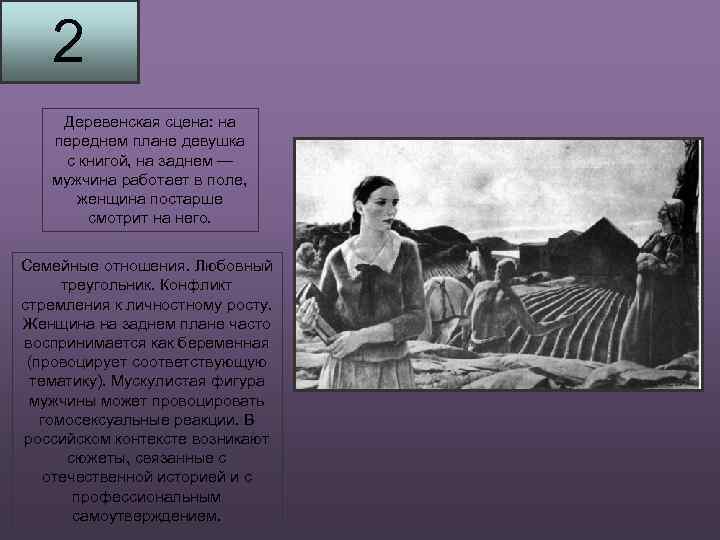

2 Village scene: in the foreground there is a girl with a book, in the background there is a man working in the field, an older woman is looking at him. Family relationships. Love triangle. Conflict of desire for personal growth. The woman in the background is often perceived as pregnant (provoking the corresponding theme). A man's muscular figure can provoke homosexual reactions. In the Russian context, subjects related to national history and professional self-affirmation arise.

2 Village scene: in the foreground there is a girl with a book, in the background there is a man working in the field, an older woman is looking at him. Family relationships. Love triangle. Conflict of desire for personal growth. The woman in the background is often perceived as pregnant (provoking the corresponding theme). A man's muscular figure can provoke homosexual reactions. In the Russian context, subjects related to national history and professional self-affirmation arise.

3 BM On the floor next to the couch is a crouched figure, most likely a boy, and a revolver on the floor next to it. The perceived gender of a character may indicate latent homosexual attitudes. Problems of aggression, in particular, self-aggression, as well as depression, suicidal intentions.

3 BM On the floor next to the couch is a crouched figure, most likely a boy, and a revolver on the floor next to it. The perceived gender of a character may indicate latent homosexual attitudes. Problems of aggression, in particular, self-aggression, as well as depression, suicidal intentions.

3 GF A young woman stands near the door, holding out her hand to it; the other hand covers the face. Depressive feelings.

3 GF A young woman stands near the door, holding out her hand to it; the other hand covers the face. Depressive feelings.

4 A woman hugs a man by the shoulders; the man seems to be trying to escape. A wide range of feelings and problems in the intimate sphere: themes of autonomy and infidelity, the image of men and women in general. A half-naked female figure in the background, when she is perceived as a third character, and not as a picture on the wall, provokes plots related to jealousy, a love triangle, and conflicts in the field of sexuality.

4 A woman hugs a man by the shoulders; the man seems to be trying to escape. A wide range of feelings and problems in the intimate sphere: themes of autonomy and infidelity, the image of men and women in general. A half-naked female figure in the background, when she is perceived as a third character, and not as a picture on the wall, provokes plots related to jealousy, a love triangle, and conflicts in the field of sexuality.

5 A middle-aged woman peers through a half-open door into an old-fashioned furnished room. Reveals the range of feelings associated with the image of the mother. In the Russian context, however, social themes related to personal intimacy, security, and the vulnerability of personal life from prying eyes often appear.

5 A middle-aged woman peers through a half-open door into an old-fashioned furnished room. Reveals the range of feelings associated with the image of the mother. In the Russian context, however, social themes related to personal intimacy, security, and the vulnerability of personal life from prying eyes often appear.

6 BM A short elderly woman stands with her back to a tall young man who has lowered his eyes guiltily. A wide range of feelings and problems in the mother-son relationship.

6 BM A short elderly woman stands with her back to a tall young man who has lowered his eyes guiltily. A wide range of feelings and problems in the mother-son relationship.

6 GF A young woman sitting on the edge of the sofa turns around and looks at a middle-aged man standing behind her with a pipe in his mouth. The painting was intended to be symmetrical to the previous one, reflecting the father-daughter relationship. However, it is not perceived so unambiguously and can actualize quite different options for relations between the sexes.

6 GF A young woman sitting on the edge of the sofa turns around and looks at a middle-aged man standing behind her with a pipe in his mouth. The painting was intended to be symmetrical to the previous one, reflecting the father-daughter relationship. However, it is not perceived so unambiguously and can actualize quite different options for relations between the sexes.

7 BM A gray-haired man looks at a young man who stares into space. Reveals the father-son relationship and the resulting relationship to male authorities.

7 BM A gray-haired man looks at a young man who stares into space. Reveals the father-son relationship and the resulting relationship to male authorities.

7 GF A woman sits on a couch next to a girl, talking or reading something to her. A girl with a doll in her hands looks to the side. Reveals the relationship between mother and daughter, and also (sometimes) to future motherhood, when the doll is perceived as a baby. Sometimes the plot of a fairy tale is inserted into the story, which the mother tells or reads to her daughter, and, as Bellak notes, this fairy tale turns out to be the most informative.

7 GF A woman sits on a couch next to a girl, talking or reading something to her. A girl with a doll in her hands looks to the side. Reveals the relationship between mother and daughter, and also (sometimes) to future motherhood, when the doll is perceived as a baby. Sometimes the plot of a fairy tale is inserted into the story, which the mother tells or reads to her daughter, and, as Bellak notes, this fairy tale turns out to be the most informative.

8 BM A teenage boy in the foreground, a gun barrel visible to the side, a blurry surgical scene in the background. Effectively brings up themes related to aggression and ambition. Failure to recognize a gun indicates problems with controlling aggression.

8 BM A teenage boy in the foreground, a gun barrel visible to the side, a blurry surgical scene in the background. Effectively brings up themes related to aggression and ambition. Failure to recognize a gun indicates problems with controlling aggression.

8 GF A young woman sits, leaning on her hand, and looks into space. Can reveal dreams about the future or current emotional background. Bellak considers all the stories on this table to be superficial, with rare exceptions.

8 GF A young woman sits, leaning on her hand, and looks into space. Can reveal dreams about the future or current emotional background. Bellak considers all the stories on this table to be superficial, with rare exceptions.

9 BM Four men in overalls lie side by side on the grass. Characterizes relationships between peers, social contacts, relationships with a reference group, sometimes homosexual tendencies or fears, social prejudices.

9 BM Four men in overalls lie side by side on the grass. Characterizes relationships between peers, social contacts, relationships with a reference group, sometimes homosexual tendencies or fears, social prejudices.

9 GF A young woman with a magazine and a purse in her hands looks from behind a tree at another smartly dressed woman, even younger, running along the beach. Reveals relationships with peers, often rivalry between sisters or conflict between mother and daughter. Can identify depressive and suicidal tendencies, suspicion and hidden aggressiveness, even paranoia.

9 GF A young woman with a magazine and a purse in her hands looks from behind a tree at another smartly dressed woman, even younger, running along the beach. Reveals relationships with peers, often rivalry between sisters or conflict between mother and daughter. Can identify depressive and suicidal tendencies, suspicion and hidden aggressiveness, even paranoia.

10 A woman's head is on her husband's shoulder. Relationships between a man and a woman, sometimes hidden hostility towards the partner (if the story is about separation). The perception of the two men in the painting suggests homosexual tendencies.

10 A woman's head is on her husband's shoulder. Relationships between a man and a woman, sometimes hidden hostility towards the partner (if the story is about separation). The perception of the two men in the painting suggests homosexual tendencies.

11 The road running along the gorge between the rocks. There are obscure figures on the road. The head and neck of a dragon protrudes from the rock. Actualizes infantile and primitive fears, anxieties, fear of attack, and general emotional background.

11 The road running along the gorge between the rocks. There are obscure figures on the road. The head and neck of a dragon protrudes from the rock. Actualizes infantile and primitive fears, anxieties, fear of attack, and general emotional background.

12 M A young man lies on a couch with his eyes closed, an elderly man is leaning over him, his hand is extended to the face of the man lying. Attitudes towards elders, towards authorities, fear of dependence, passive homosexual fears, attitude towards a psychotherapist.

12 M A young man lies on a couch with his eyes closed, an elderly man is leaning over him, his hand is extended to the face of the man lying. Attitudes towards elders, towards authorities, fear of dependence, passive homosexual fears, attitude towards a psychotherapist.

12 F Portrait of a young woman, behind her is an elderly woman in a headscarf with a strange grimace. Relationship to mother, although most often the woman in the background is described as the mother-in-law.

12 F Portrait of a young woman, behind her is an elderly woman in a headscarf with a strange grimace. Relationship to mother, although most often the woman in the background is described as the mother-in-law.

12 BG A boat tied to a river bank in a wooded environment. There are no people. Bellak considers this table useful only in identifying depressive and suicidal tendencies

12 BG A boat tied to a river bank in a wooded environment. There are no people. Bellak considers this table useful only in identifying depressive and suicidal tendencies

3 BM A young man stands with his face covered with his hands, behind him on the bed is a half-naked female figure. Effectively identifies sexual problems and conflicts in men and women, fear of sexual aggression (in women), feelings of guilt (in men).

3 BM A young man stands with his face covered with his hands, behind him on the bed is a half-naked female figure. Effectively identifies sexual problems and conflicts in men and women, fear of sexual aggression (in women), feelings of guilt (in men).

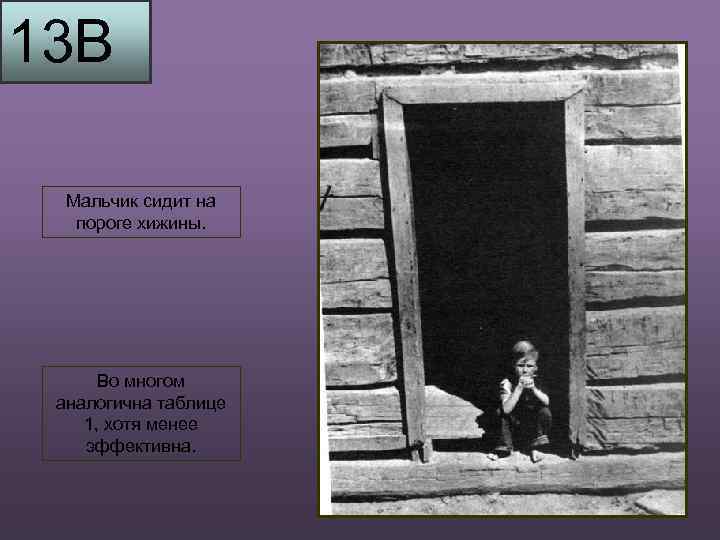

13 B A boy is sitting on the threshold of a hut. In many ways similar to Table 1, although less effective.

13 B A boy is sitting on the threshold of a hut. In many ways similar to Table 1, although less effective.

13 G The girl goes up the steps. Bellak considers this table to be of little use, like other purely teenage TAT tables.

13 G The girl goes up the steps. Bellak considers this table to be of little use, like other purely teenage TAT tables.

15 An elderly man with his hands down stands among the graves. Attitude to the death of loved ones, own fears of death, depressive tendencies, hidden aggression, religious feelings.

15 An elderly man with his hands down stands among the graves. Attitude to the death of loved ones, own fears of death, depressive tendencies, hidden aggression, religious feelings.

16 Clean white table. Provides rich, versatile material, but only for subjects who do not experience difficulties with verbal expression of thoughts.

16 Clean white table. Provides rich, versatile material, but only for subjects who do not experience difficulties with verbal expression of thoughts.

18 BM A man is grabbed from behind by three hands, the figures of his opponents are not visible. Identifies anxieties, fear of attack, fear of homosexual aggression, and the need for support.

18 BM A man is grabbed from behind by three hands, the figures of his opponents are not visible. Identifies anxieties, fear of attack, fear of homosexual aggression, and the need for support.  18 GF A woman has her hands around another woman's throat, seemingly pushing her down the stairs. Aggressive tendencies in women, conflict between mother and daughter.

18 GF A woman has her hands around another woman's throat, seemingly pushing her down the stairs. Aggressive tendencies in women, conflict between mother and daughter.

20 A lonely male figure at night near a lantern. As with Table 14, Bellak points out that the figure is often perceived as female, but our experience does not confirm this. Fears, feelings of loneliness, sometimes assessed positively.

20 A lonely male figure at night near a lantern. As with Table 14, Bellak points out that the figure is often perceived as female, but our experience does not confirm this. Fears, feelings of loneliness, sometimes assessed positively.

Interpretation of results By completing or structuring an incomplete or unstructured situation, the individual manifests his aspirations, dispositions and conflicts in this. When writing a story, the narrator usually identifies with one of the characters, and that character's desires, aspirations, and conflicts may reflect the desires, aspirations, and conflicts of the narrator. Sometimes the narrator's dispositions, aspirations, and conflicts are presented in implicit or symbolic form. Stories have unequal significance for diagnosing impulses and conflicts. Some may contain a lot of important diagnostic material, while others may have very little or no material at all. Themes that are directly derived from the stimulus material are likely to be less significant than themes that are not directly derived from the stimulus material. Recurring themes are most likely to reflect the narrator's impulses and conflicts.

Interpretation of results By completing or structuring an incomplete or unstructured situation, the individual manifests his aspirations, dispositions and conflicts in this. When writing a story, the narrator usually identifies with one of the characters, and that character's desires, aspirations, and conflicts may reflect the desires, aspirations, and conflicts of the narrator. Sometimes the narrator's dispositions, aspirations, and conflicts are presented in implicit or symbolic form. Stories have unequal significance for diagnosing impulses and conflicts. Some may contain a lot of important diagnostic material, while others may have very little or no material at all. Themes that are directly derived from the stimulus material are likely to be less significant than themes that are not directly derived from the stimulus material. Recurring themes are most likely to reflect the narrator's impulses and conflicts.

Contraindications to the use of TAT include 1) acute psychosis or a state of acute anxiety; 2) difficulty in establishing contacts; 3) the likelihood that the client will consider the use of tests a surrogate, a lack of interest on the part of the therapist; 4) the likelihood that the client will consider this a manifestation of the therapist’s incompetence; 5) specific fear and avoidance of testing situations of any kind; 6) the possibility that the test material stimulates the expression of excessive problematic material at too early a stage; 7) specific contraindications related to the specific dynamics of the psychotherapeutic process at the moment and requiring postponing testing until later

Contraindications to the use of TAT include 1) acute psychosis or a state of acute anxiety; 2) difficulty in establishing contacts; 3) the likelihood that the client will consider the use of tests a surrogate, a lack of interest on the part of the therapist; 4) the likelihood that the client will consider this a manifestation of the therapist’s incompetence; 5) specific fear and avoidance of testing situations of any kind; 6) the possibility that the test material stimulates the expression of excessive problematic material at too early a stage; 7) specific contraindications related to the specific dynamics of the psychotherapeutic process at the moment and requiring postponing testing until later

Advantages and disadvantages of TAT Disadvantages Advantages Labor-intensive procedure for carrying out the Richness, depth and variety of diagnostic information obtained using TAT Labor-intensive processing and analysis of results Possibility to combine various interpretative schemes or improve and supplement them High requirements for the qualifications of a psychodiagnostician Independence of the procedure for processing results from the examination procedure

Advantages and disadvantages of TAT Disadvantages Advantages Labor-intensive procedure for carrying out the Richness, depth and variety of diagnostic information obtained using TAT Labor-intensive processing and analysis of results Possibility to combine various interpretative schemes or improve and supplement them High requirements for the qualifications of a psychodiagnostician Independence of the procedure for processing results from the examination procedure

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) is a projective psychodiagnostic technique developed in the 1930s at Harvard by Henry Murray and Christiane Morgan. The purpose of the methodology was to study the driving forces of personality - internal conflicts, drives, interests and motives.

The Drawing Apperception Test (PAT) is a compact modified version of G. Murray's Thematic Apperception Test, which takes little time for examination and is adapted to the working conditions of a practical psychologist. A completely new stimulus material has been developed for it, which consists of contour plot pictures. They schematically depict human figures.

The drawn apperception test, due to its greater brevity and simplicity, has found application in family counseling, in providing socio-psychological assistance to pre-suicide victims, as well as in the neurosis clinic and forensic psychiatric examination.

The technique can be used both in individual and group examinations, with both adults and adolescents from 12 years of age. Testing can be done by listening to stories and writing them down, but you can also give a task and ask the person to write down their answers themselves. Then he (or a group of people being examined) is asked to sequentially, according to numbering, look at each picture and write a short story about how he interprets the contents of the picture.

Testing time is not limited, but should not be unduly long in order to obtain more immediate answers.

Drawing apperception test (PAT) by G. Murray. And also a methodology for studying conflict attitudes, B.I. Hassan (based on the RAT test):

Instructions.

Carefully examine each drawing in turn and, without limiting your imagination, compose a short story for each of them, which will reflect the following aspects:

- What's happening at the moment?

- Who are these people?

- What are they thinking and feeling?

- What led to this situation and how will it end?

Do not use well-known plots taken from books, theater plays or films - come up with something of your own. Use your imagination, ability to invent, wealth of fantasy.

Test (stimulus material).

Processing the results.

Analysis of the subject’s creative stories (oral or written) allows us to identify his identification (usually unconscious identification) with one of the “heroes” of the plot and the projection (transfer into the plot) of his own experiences. The degree of identification with a plot character is judged by the intensity, duration and frequency of attention paid to the description of this particular plot participant.

Signs based on which one could conclude that the subject identifies himself to a greater extent with this hero include the following:

- thoughts, feelings, and actions are attributed to one of the participants in the situation that do not flow directly from the given plot presented in the picture;

- one of the participants in the situation is given significantly more attention during the description process than the other;

- against the background of approximately the same amount of attention paid to the participants in the proposed situation, one of them is assigned a name, and the other is not;

- against the background of approximately the same amount of attention paid to the participants in the proposed situation, one of them is described using more emotionally charged words than the other;

- against the background of approximately the same amount of attention paid to the participants in the proposed situation, one of them has direct speech, and the other does not;

- against the background of approximately the same amount of attention paid to the participants in the proposed situation, one is described first, and then the others;

- if the story is compiled orally, then a more emotional attitude towards the hero, with whom the subject identifies himself to a greater extent, is manifested, manifested in the intonations of the voice, in facial expressions and gestures;

- if the story is presented in written form, the features of the handwriting can also reveal those facts with which there is greater identification - the presence of strikeouts, blots, deterioration of handwriting, increased slope of the lines up or down compared to normal handwriting, any other obvious deviations from normal handwriting, when the subject writes in a calm state.

It is not always possible to easily detect a more significant character in the description of a picture. Quite often, the experimenter finds himself in a situation where the volume of written text does not allow him to judge with sufficient confidence who is the hero and who is not. There are other difficulties. Some of them are described below.

- Identification shifts from one character to another, that is, in all respects, both characters are considered in approximately the same volume, and, first, one person is completely described, and then completely another (B.I. Khasan sees this as a reflection of the instability of the subject’s ideas about himself) .

- The subject identifies himself with two characters at the same time, for example, with “positive” and “negative” - in this case, in the description there is a constant “jumping” from one character to another (dialogue, or simply description) and it is precisely the opposite qualities of the participants in the plot that are emphasized (this may indicate the author’s internal inconsistency, a tendency to internal conflicts).

- The object of identification can be a character of the opposite sex or an asexual character (person, creature, etc.), which can in some cases, with additional confirmation in the text, be regarded as various problems in the intergender sphere of the individual (the presence of fears, problems with self-identification, painful dependence on a subject of the opposite sex, etc.).

- In a story, the author can emphasize his lack of identification with any of the participants in the plot, taking the position of an outside observer, using statements like: “Here I am observing the following picture on the street...”. B.I. Khasan proposes to consider the heroes in this case as the antipodes of the subject himself. At the same time, it can be assumed that this is not the only possible interpretation. So, for example, the position of an outside observer can be taken by a person whose system of defense mechanisms of his Ego does not allow him to realize the presence of qualities in himself that he attributes to others, or this may be the result of fear of such situations and the dissociation mechanism is triggered.

The subject may associate this or that picture with his own life situation, causing frustration. In this case, the heroes of the story realize the needs of the narrator himself, unrealized in real life. It also happens the other way around - the story describes obstacles that prevent the fulfillment of needs.